Pygmalion

Acte de ballet

Libretto by Ballot de Sauvot

First performance: Académie Royale de Musique, Paris, 1748

Cast:

Pygmalion, haute-contre

Céphise, soprano

La Statue, soprano

L'Amour, soprano

Chorus

Dancers

Orchestra:

2 flutes (double on piccolos), 2 oboes, bassoon, strings, and continuo

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

Rameau's one-act opera-ballet Pygmalion was written in a mere eight days, according to some reports, and it was premiered in 1748 at the Académie Royale de Musique, an institution established by Lully in the previous century. The directors of the Opéra, as the Académie was popularly called, knew that a new work by Rameau would be a box office success. As it turned out, this small drama was one of the greatest successes of the composer's career and was remounted many times during the eighteenth century.

Rameau had appeared suddenly and unexpectedly in the world of theater in 1733, when, at the age of 50, he achieved enormous fame and popular success with the premiere of his first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie. Until then, he had been known to connoisseurs for his harpsichord music, some vocal works, and particularly for his treatises on music theory, which are still the basis of much of the theory teaching today. But Hippolyte was a shock to the musical establishment in Paris. Few people knew that this theorist could write music of such depth and brilliance, music in which even the colorful orchestration was unprecedented. Some immediately recognized him as the greatest opera composer since Lully. The composer Campra is reported to have said, "There is enough music in this to make ten operas; this man will eclipse us all." For others, the music was bizarre, overly "learned," and "baroque" (a pejorative term at the time), a threat to the long tradition established by Lully. The musical public quickly split into two opposed camps, ardent supporters of Lully and equally ardent supporters of Rameau. But over time, as more of his operas appeared, Rameau firmly established his reputation as the greatest French composer of his day, even for some as the "new Lully."

Rameau spent his life mostly outside the circle of the French royal court. Very few details are known about his early career. (Even his wife claimed to know little about his youth.) Most of it was spent outside Paris as an organist, and when he finally did settle in the capital in the early 1720's, he appears to have had no regular position for nearly a decade. For most of his later career, he enjoyed the patronage of the wealthy tax collector and financier Le Riche de la Pouplinière, conducting his orchestra, living for some years in his mansion, and socializing with other artists and luminaries in La Pouplinière's circle, including Voltaire and Rousseau. Rameau was known as a thorny character with no close friends but was nonetheless a central figure in that circle. According to Rousseau, "Rameau's will was law in that house."

It was there that Rameau met the librettist of Pygmalion, the amateur poet Ballot de Sauvot. For their commission, the two men adapted Ovid's story of Pygmalion, basing their libretto not on Ovid himself but on another opera libretto from a half century earlier. Rameau, the more experienced and more famous collaborator, controlled the process and demanded many changes in the libretto: characters were dropped, the roles of Céphise and Amour were added, and there were many alterations to the text.

Dance in this one-act drama is of equal importance to singing, with some sections of the story given over to one medium and some to the other. The sculptor Pygmalion has angered Venus by not giving in to love, and, as a punishment, she causes him to fall in love with his own inanimate statue of a woman. Following a brilliant overture, the scene opens on Pygmalion's grief. He has fallen in love with the statue and cries out to "cruel Love" in a beautiful, emotionally moving air that is complex, highly detailed, and sensitively orchestrated. He is interrupted by the jealous Céphise, who wants his attentions, but, left alone again, Pygmalion returns to thoughts of the statue. The music shifts to major as he prays to Venus. She answers indirectly, as sustained E major chords announce the presence of a god, and the statue begins to come to life and profess her love for Pygmalion. The god of Love sings an air telling Pygmalion that his wish has been granted. There follows a sequence of brief dance fragments, each leading into the next and growing successively longer -- a gentle gavotte, a menuet, a faster gavotte, chaconne, loure, passepied, rigaudon, sarabande and tambourin -- as the statue is taught how to move. The populace joins the pair to celebrate the miracle, singing in chorus, "Love has triumphed!" Following Pygmalion's final air, "Reign, o Love," the celebration returns to the ballet, concluding with a brilliant contredanse.

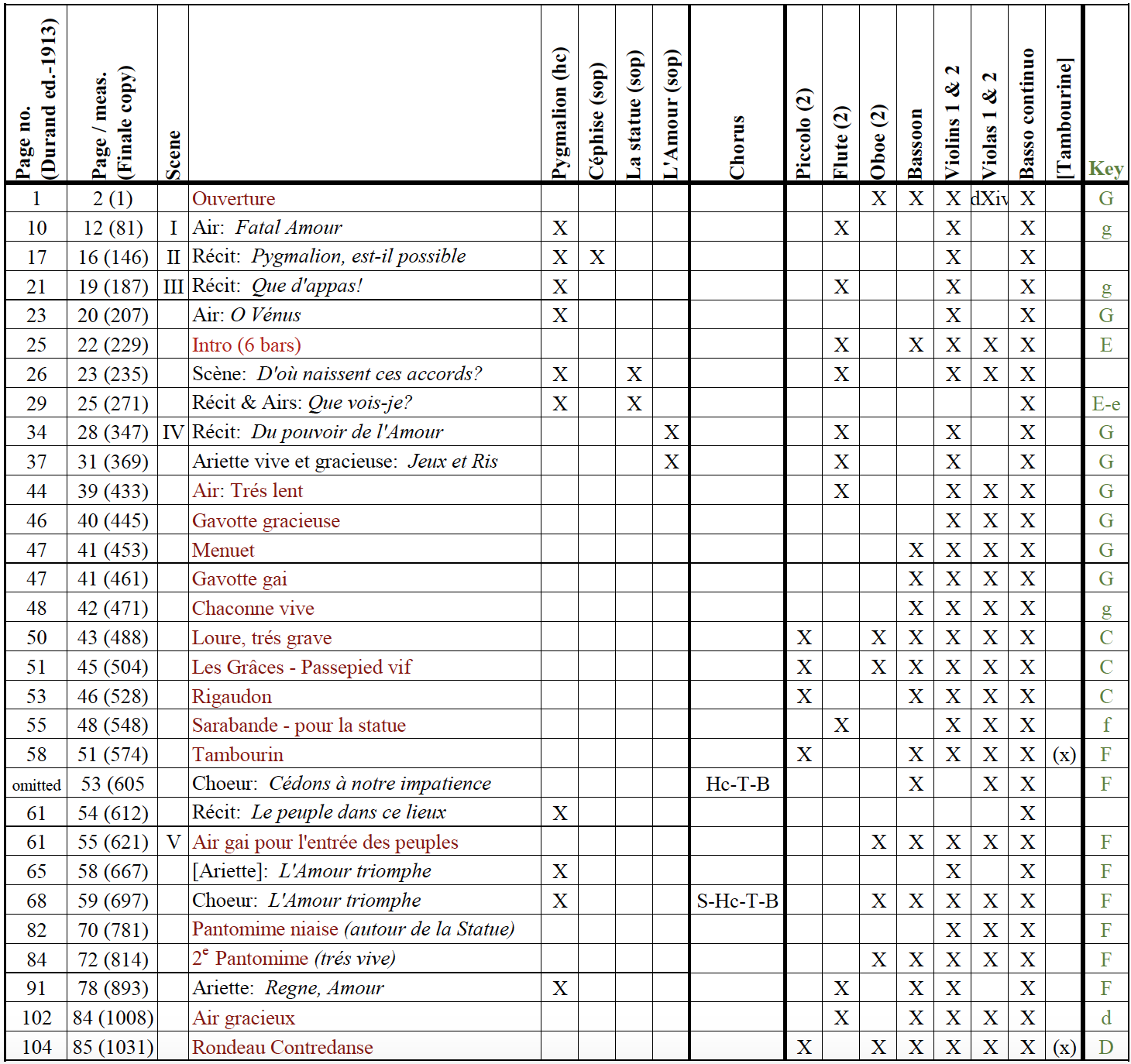

Orchestration Chart

This chart gives an overview of the work, showing which soloists and instruments are in each movement. It has also been useful in planning rehearsals, since one can see at a glance all the music that a particular musician plays. Red X's indicate major solo moments for a singer. An X in parentheses indicates that the use of that instrument is ad libitum.

This is a preview of the beginning of the chart. You can download or view a PDF of the whole chart here.

© Boston Baroque 2020

Boston Baroque Performances

Pygmalion

March 6 & 7, 2009

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Lawrence Williford - Pygmalion

Kristen Watson - Céphise

Meredith Hall - The statue

Marjorie Folkman - dancer & choreographer

Rob Besserer - dancer